Lazy Divide and Conquer

Hi all!

Today I’ll be presenting a simple, but interesting Divide and Conquer trick that lets you process 2D range updates and range queries quickly and with low memory usage.

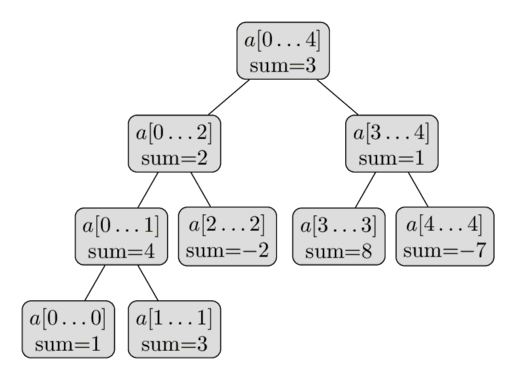

The basis of this form of Divide and Conquer is the segment tree, except instead of being used to process queries and updates online, we’ll be traversing the segment tree im a way similar to a BFS or DFS search. This allows us to use a 1D data structure to compute the answers to each query. This usually results in an improved memory complexity (usually by a log factor) along with a smaller hidden constant in the time complexity (which I believe is due to better cache locality).

To motivate the algorithm, I’ll present a sample problem:

Given an \(N \times N\) grid \(A\) (all initially zeros), process \(Q\) operations of the following types:

- Given the integers \(l,r,d,u,v\), assign \(A_{i,j} := A_{i,j} + v\) for all \(l \le i \le r, d \le j \le u\)

- Given the integers \(l,r,d,u\), output the value \(\sum_{i=l}^r \sum_{j=d}^u A_{i,j}\)

Note that this question is simply asking to support 2 types of operations on a 2D grid: 2D range increment and 2D range sum. From now on, the problem will be referred to in this context.

Additionally, let’s assume that \(l=r\) and \(d=u\) for every update, so we don’t need to worry about range increments. Then, after we solve this sub-problem, we’ll generalize our solution to work for any \(l,r\) and \(d,u\).

Our solution to the sub-problem works by performing Divide and Conquer on the first dimension (l-r), and then using a segment tree (fenwick tree works too in this case) to perform range queries across the second dimension (d-u).

We start by considering the entire range of values across the first dimension (setting \(l=1,r=N\)) and all operations. We then apply all the operations in order, applying all updates but only computing queries which occupy the whole l-r range. Note that this means we effectively treat each operation as 1-dimensional, which means we only need to consider the d-u dimension of each operation.

Finally, we divide our range into two halves, and then propagate all queries and updates to a half if it partially or completely covers it, but not if it covers the whole l-r range already.

Below is some pseudocode, which some may find more helpful than the wordy explanation:

solve(l, r, operations): # Call solve(1, N, operations) to compute all answers

covers(op):

return op.l <= l and r <= op.r

reset_segment_tree()

for op in operations:

if op is update:

update_segment_tree(op.d, op.v)

else if op is query and covers(op):

ans[op.index] += query_segment_tree(op.d, op.u)

left = []

right = []

mid = (l + r) / 2

for op in operations:

if not covers(op):

if op.l <= mid:

left.append(op)

if op.r > mid:

right.append(op)

solve(l, mid, left)

solve(mid+1, r, right)

Complexity Analysis

In our Divide and Conquer, each update is either pushed to the left or right (and never both) recursive call. And as the recursion will only ever go \(\mathcal{O}(\log{N})\) layers deep, each update must be processed at most \(\mathcal{O}(\log{N})\) times. For the queries, we can observe that for a given query \(l,r,d,u\), the ranges that the query will be processed at are identical to the ranges considered by a 1D segment tree processing a range query from index \(l\) to \(r\). This means that each query will be processed at moat \(\mathcal{O}(\log{N})\) times. Thus, the overall time complexity of the solution is \(\mathcal{O}(Q \log^2{N})\)

As for memory usage, the only memory we need to worry about is the segment tree and the list of operations held in the stack when performing the Divide and Conquer. The first source of memory usage clearly uses \(\mathcal{O}(N)\) memory, but the second is a bit more complicated. Our worst case is when all of our operations are present at each level of recursion (i.e. \(l=r=1\) for all operations), which would give us \(\mathcal{O}(Q \log{N})\) operations being stored at once as there are \(\mathcal{O}(\log{N})\) levels of recursion in our Divide and Conquer.

Thus, the total memory complexity should be \(\mathcal{O}(N + Q \log{N})\).

Now, let’s generalize our updates to any \(l,r,d,u\). You may think that this will make our code quite complicated, as it would involve some form of offline lazy propagation (given how our algorithm resembles updates and queries on segment trees). However, there already exists a powerful trick that lets us perform range updates on a segment tree without lazy propagation, and this is something we can adapt to our algorithm as well.

The only real issue preventing us from just propagating updates to both sides is that a single update covering the entire range 1-N in the 1st dimension will propagate to \(N\) copies of itself by the bottom layer. Obviously, applying every single update \(N\) times will not work, but there is a way to optimize: treating updates like queries.

If any update completely covers the range we’re currently on, we won’t propagate it further. Instead, we apply all the operations again, but only consider updates that completely cover the range and ALL queries (you may notice that this is the reverse of what we were doing earlier, where we only considered queries covering the range but ALL updates). Thus, the expanded pseudocode would be the following (note that new/changed lines are marked with a * at the end):

Note that this time, our segment tree also needs to support range increment.

solve(l, r, operations): # Call solve(1, N, operations) to compute all answers

covers(op):

return op.l <= l and r <= op.r

reset_segment_tree()

for op in operations:

if op is update:

update_segment_tree(op.d, op.u, op.v) *

else if op is query and covers(op):

ans[op.index] += query_segment_tree(op.d, op.u)

reset_segment_tree() *

for op in operations: *

if op is query: *

ans[op.index] += query_segment_tree(op.d, op.u) *

else if op is update and covers(op): *

update_segment_tree(op.d, op.u, op.v) *

left = []

right = []

mid = (l + r) / 2

for op in operations:

if not covers(op):

if op.l <= mid:

left.append(op)

if op.r > mid:

right.append(op)

solve(l, mid, left)

solve(mid+1, r, right)

Lastly, if you are in need of some code and a sample problem, here is my solution to a problem that uses this trick. Note that this problem varies slightly from the given sample problem in that we only need to check if the sum of a subrectangle is \(>0\), which also means that our lazy function can be slightly incorrect but still be accepted since the exact sum is not relevant to our answer.

Extra Notes

The biggest note I have for the blog is (surprisingly enough) the hidden constant of the runtime. While in my experience, this trick is preferable to using 2D data structures such as sparse fenwick tree, 2D segment tree, and segment tree of binary search trees, it still has a large constant factor. This is because updates have be done and undone multiple times, which means your 1D data structure needs to be very efficient for a low runtime. This also means that for some coders who are very advanced with 2D data structures, this trick may not improve runtime.

Additionally, I want to note the motivation I had for this trick. The non-lazy version (where you only have to process point updates), is (to my understanding) a well-known trick first presented by CDQ in her China TST Paper from 2008. Meanwhile, the lazy version was just the result of me slapping together CDQ Divide and Conquer with some funny segment tree shenanigans :)